01 Sep Renaissance Beautification Rituals Revealed

The Renaissance was a period in which the senses were fully reborn. Beginning in Florence, Italy in the 1400s, it ushered the search for perfection of form through the harmony of proportions, the establishment of anatomical standards and with it, it brought about a new ideal of female beauty. Art had become philosophy and so the love of physical beauty had indeed pervaded every aspect of life.

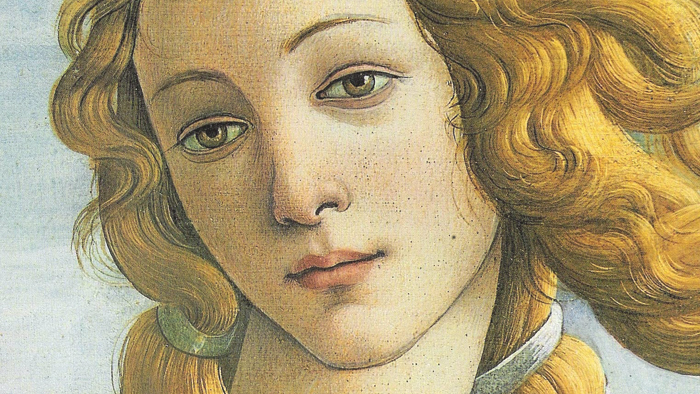

Delicate, round and supple, yet proportional features were highly prized during the cultural revolution. According to theoreticians, the perfect face was to be set on a long neck. It must be fine and oval, with a high forehead, thin eyebrows, a well defined, straight and thin nose and a small mouth. Skin was to be pale and translucent, yet cheeks, lips and nails were to be a radiating red. Hair was to be honey blonde and curly, epitomising youthfulness. Machiavelli had even claimed that the hands of a women could only be beautiful if “long, lined with tiny, light-coloured veins, ending with slender fingers”.

And as with any other era, with an ideal standard of female beauty, came the pressure for women to look beautiful and attractive. For the women of the Renaissance, it was a duty, assigned to them by God, that they were obliged to fulfil.

And so we ask, how did the women attain their looks? What were the secrets behind their beauty rituals?

THE MIGHTY HIGH FOREHEAD:

As a high forehead was highly appreciated during these times, women would resort to different beautification methods in order to raise their hairlines. Some women would pluck out their hairs, one by one, from their natural hairline all the way back to the crowns of their heads. For those not so fond of plucking, poultices of vinegar, mixed with quicklime or cat dung were applied, which at times would also remove some of the skin as well as the hair!

LILY-LIKE TRANSLUCENT SKIN:

Fair skin was another ideal type of beauty, representing wealth, youthfulness and health. For those not blessed with naturally pale skin, rather dangerous compounds such as lead oxide, hydroxide, carbonate, mercury and vermillion would be applied to the face to achieve the coveted pale completion. In particular, mercury granted the illusionary effect of innocence, fertility and virtue, blurring age-ing process and ‘airbrushing’ blemishes, freckles and brown spots. White lead, also known as ‘Venetian Ceruse’ and ‘Spirits of Saturn’ was another effective skin-whitener. However, these highly in demand skin-enhancing cosmetic applications would have devastating fatal effects on health at times leading to scarring, wrinkled leathery skin, facial muscle paralysis, headaches and ultimately led to early deaths. One beauty regime that would help enhance this translucent effect was the application of raw eggs to the face as a primer. Next, lead and vinegar were mixed together to make a thick, ceruse-coloured foundation which was applied liberally to the face and neck. Women would have to remain immobile and cautious in order to avoid this new skin from cracking and flaking. If women wanted to achieve a marble statuesque look, they would apply blue “veins” using a thin brush to the forehead and breasts! Other advise on achieving fair skin was to wash in your own urine or with a mixture of rosemary and wine. Another secret beauty ritual for pale skin was to apply leeches to the ears. The leeches would drain the blood from the head, thus leaving the women their much desired pale look. However stomach-churning it may sound, leeches were in fact a far more healthier alternative to some of the more harmful ways of attaining a pale complexion.

FLUSHED CHEEKS AND ROSY LIPS

Even though an overall pale look was heavily desired, the women of the Renaissance still used a touch of colour on their cheekbones, which gave off a natural blushing demonstrating shame and modesty which were desirable traits. Mercuric sulphide was present in a rouge recipe and this mixture was applied lightly to the cheekbones, and in some cases to their chests to draw attention to the bust. For the lips, ‘Vermillion rouge’ another mercury based colorant was used, mixed with fruit juice, alkanet roots or cochineal for a radiating glow.

WIDE & DOE-EYED LIMPID LOOK

Women during this time also used their Renaissance version of eyeliner and mascara. Kohl, a dark mineral based powder, was a popular substance for eyeliner. Women oiled their eyelashes in order to create the illusion of darker, thicker eyelashes. Italian women also practiced putting drops of belladonna, a herb, into their eyes. It would create the desired effect of making their eyes sparkle and make their eyes look wider. Unfortunately, this pupil dilating effect by belladonna was caused by its toxic ingredient ‘atropine’, which over an extended period of usage would cause visual disturbances, increased heart rates, leading to poisoning and permanently harmed eye vision.

LUSTROUS LOCKS

Honey blond hair was considered the ideal hair colour during this period of time. Women thus resorted to colouring their hair through different bleaching methods. They used a variety of ingredients from saffron to sulphur and turmeric to give their hair the desired look. Firstly, they would apply a product with lye in it to rid their hair of its natural colour before applying the dye. They would then spend long periods of time under the sun to bleach their hair. To avoid tanning their skin or getting freckles, women would wear layers of clothing and wear wide-brimmed hats with the top cut out to expose only the hair to the sun, which were known as the Venetian Hats. Other beauty rituals included using a mixture of urine, rhubarb, cumin seed and celandine. In order to rid grey hairs, a recipe included boiling quicklime in powder, lead oxide with gold and silver and applying it to the hair, to later be washed off with no soap and repeated every week. As hair was not to frequently washed, fragranced powders were applied to natural hairs and wigs. Wigs were worn as a result of balding due to the side-effects of mercury and lead usage.

TEETH:

There had been several different teeth-whitening methods. One such recipe advised mixing pumice stone, brick and coal followed by a rubbing of the teeth vigorously. Another teeth-whitening ritual was to use “dragon-blood” mixed with red coral powder and white whine tartar. During the reign Elizabeth I in England, it become fashionable to to paint the teeth black. Not only had this ‘tooth decay’ highlighted the fact that one could afford sweets, but it was also an effective cover-up for enamel that had been worn off of teeth from some of the more destructive whitening-rituals.

BEAUTY MARKS:

Beauty marks and beauty patches were also used in beauty regimes during the Renaissance. In an effort to conceal pimples or other imperfections, beauty marks were drawn on. Beauty patches, made of fabric, were cut into various shapes, stars, moons or circles to cover holes in the skin that were caused by the use of lead make-up.

ROYAL COSMETIC TIPS FROM THE RENAISSANCE BEAUTY ICONS:

The royal women of Renaissance were renowned for their looks and were considered beauty icons of the era. Many Renaissance women followed their beauty regimes religiously. Catherine de Medici used pigeon dung on her to face to achieve a young, dewy complexion. Mary Queen of Scots was said to have bathed in wine to keep her youthful appearance. Diane de Poitiers’ fountain of youth was to drink gold.