28 Apr The Opulence of Mughal Women

The founder of the Mughal dynasty, Zahirud-din Mohammed Babur ‘the Tiger’, had been a descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan, the mighty Emperors of Central Asia. Descending from the Fergana Valley and later from the snow-capped mountains at Kabul, in 1525 Babur crossed the Indus and swept into Punjab, the northwest’s strategic gateway. His eyes and ears had been captivated by the extraordinary Indian landscape, flora, fauna, architecture and people, and from that moment on, he began the Mughal dynasty which left a profound influence on the subcontinent.

From the sixteenth to nineteenth century, the Mughal Empire ruled large swaths of the Indian subcontinent. However, its significance lay not only in its size, it too presided over an important golden age of arts, literature and culture, which represented a blending of Indian and Persian styles.

The Mughal grandeur famed worldwide really began with the imperial Mughal women themselves; they had personified the opulence and splendour of the empire. Here are ten facts you may not have known about the royal Mughal ladies!

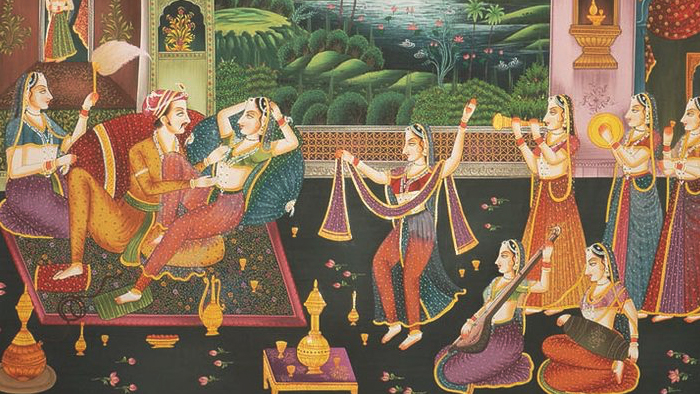

- During the Mughal era, the custom of purdah, the “curtain” concealing women from the public, had been compulsory for all women—it was considered an essential part of a respectable way of life. Mughal rulers took particular care in having their harem, known as zenanas, furnished with the most beautiful women who could be procured for love or money. Mughal courts depicted their women in their miniatures with the exotic, and almost unattainable beauty they were conceived to possess. As a cosmopolitan mix, the women of the Mughal zenanas hailed from different corners of the empire, from diverging cultural milieus, speaking diverse languages. They were all too, of differing kinds of beauty.

- The Mughal zenanas were not devoid of intellectual and well-educated ladies, and they usually kept pace with the learned Mughal Emperors and princes. Although they numbered a few, they received education from learned intellectuals, studied astronomy, mathematics, the Qu’ran, maintained libraries, spoke Turki and Persian, encouraged mass education and some even went on to produce great literary works. Perhaps least known, many mothers, daughters and wives of the Mughal Emperors had been the driving forces behind them, who protected and advanced the emperors by their own will, talents and ambitions.

- The increased wealth of Mughal courts brought great prosperity to the women in the zenena. Some of the Mughal Queens—Begums—were, by dowry, enormously wealthy in their own right and had their own masnad, throne, cooks, reception and halls. They had even maintained personal armies and rode in covered palanquins with their own fabulously ornamented retinue in the great religious processions. Other women of the zenana conducted overseas trade and each had a monthly allowance for their expenditure on jewels, clothes and cosmetics. They not only became patrons of the arts, literature, and architecture (with several ornamental mansions, tombs, bazaars, caravansaries, bathhouses, waterways, and gardens in their names), but had also propelled the fields of cosmetics and beautification.

- The imperiously beautiful and enormously talented, Nur Jahan Begum (1577-1645), the ‘Light of the World’ and Queen consort of Emperor Jahangir, ‘the World-Seizer’, played a significant role in the administration of the empire during his reign, and had been the only Mughal Queen to have her face inscribed on a coin of the realm. Nur Jahan had been an accomplished poet, traded indigo, one of the main exports of the empire, designed textiles and dressed in a style that set Mughal fashion for many years. She also never broke purdah, and even hunted tigers from the closed howdah on top of an elephant with only the barrel of her musket exposed between the curtains. As an elegant and refined Begum, Nur Jahan mastered the art of blending scents and perfumes and regularly bathed in a marble pool filled with a thousand rose petals. Some believe she had been the first to discover the legendary Itr, attar, of roses when bathing one evening. Upon noticing an oil-like substance floating upon the water, and when lowering her head, she became intoxicated by the scent of the petals. She then summoned the oil to be collected and soon after, the precious fragrance, the attar of roses, became one of the most sought-after perfumes in India.

- Mughal women embellished and decorated every inch of their bodies with different types of ornaments. They were extremely fond of exhibiting their jewels, and were said to have owned at least six to eight sets. At times, their jewelry had even hindered their movements – they had been a walking treasure house of jewels.

- Mughal women also popularized nose rings, which can be seen in most parts of India today. They also wore plenty of rings on each finger. Some rings had been so large; they covered almost two to three of their fingers. Their centerpieces were either circular or square in shape, and embedded with bulky gemstones, pure or enameled diamonds or jade. Some rings, particularly thumb-rings, featured little round mirrors, arsi, so that the women could admire their reflections.

- The Begums retained their cosmetic habits from their ancestresses in Central Asia. There had been hammams in the zenana and every Friday, they had an obligatory bath. Yet, each day, they washed their face, hands and feet and perfumed themselves quite frequently. They cleaned their teeth with the neem twig, and a tooth powder prepared with crushed pearls, musk, amber, aloeswood and camphor. They chewed paan, (betel leaves) to color their lips red, and applied missi (black powder) to their lips and gums, and occasionally to their teeth to blacken the rims so as to set their teeth off like pearls.

- Mughal garments were made up of most expensive fabrics available during the times and royal Mughal women faced no difficulty in acquiring costly materials for their outfits, as well as expert tailors to stitch their clothing. Their clothes came from foreign lands, as well as different parts of the sub-continent. Silk was brought from Persia, China, and other parts of India like Orissa, Bengal and Banaras. These garments were produced in Karkhanas, manufacturing houses, and had thousands of tailors, creating clothes for the Emperor’s household. These costly garments, embroidered beautifully with the finest needlework, were worn only a few times. The women’s costly dresses not only revealed their rank and status, but also the extent of the Emperor’s affection towards them.

- Royal Mughal princesses wore the peshwaz, a light, full-skirted gown over pajama trousers. Although its purpose was to veil, its effect was erotic, revealing more than it had concealed. It was originally presented as a ceremonial gift from the imperial court to daughters of royal houses, so admired it was adopted by dancing girls and royalty alike. Only the most superior white muslins were used to make a peshwaz, and they were called by a number of poetic names – white of clouds when the rain is spent, the white of the august moon, the white of the conch shell, the white of the jasmine flower and the white of the sea surf. The finest of all muslins had been shabnam, the muslin of morning dew from Dacca. Yards and yards of it had been laid on the palace lawns at dawn. And if it was so transparent, enough for the royal ladies to mistaken it for dew, it was made to make a peshwaz.

Bibliography

Eraly, A. (2007). The Mughal World: Life In India’s Last Golden Age. Penguin Books India: New Delhi.

Nevile P. (2000). Beyond the Veil: Indian Women in the Raj. Nevile Books: New Delhi.

Palit, M. (2000). ‘Powers Behind the Throne: Women in Early Mughal Politics’. In Faces of the Feminine in Ancient, Medieval and Modern India, by Bose, M. (pp. 201-212). Oxford University Press: New York.

Patnaik, N. (1985). A Second Paradise: Indian Courtly Life 1590-1947. Rupa & Co.: New Delhi.